Description:

Please see the video gallery for a live recording of this hearing.

Unable to Attend in Person

Statement of Roberta Cohen, Chair, Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, and Non-Resident Senior Fellow, the Brookings Institution, on China’s Repatriation of North Korean Refugees, at the Hearing of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, March 5, 2012

On behalf of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, I would like to express great appreciation to Congressman Christopher Smith and Senator Sherrod Brown for holding this hearing today to highlight the case of an estimated 30 to 40 North Koreans who fled into China and now risk being forcibly returned to North Korea where they will most assuredly be severely punished. We consider it essential to defend the fundamental rights of North Koreans to leave their country and seek asylum abroad and to call upon China to stop its forcible repatriation of North Koreans and provide them with the needed human rights and humanitarian protection to which they are entitled. The right to leave a country, to seek asylum abroad and not to be forcibly returned to conditions of danger are internationally recognized rights which North Korea and China, like all other countries, are obliged to respect.

This particular case of North Koreans has captured regional and international attention. South Korean President Lee Myung Bak has spoken out publicly against the return of the North Koreans and National Assembly woman Park Sun Young has undertaken a hunger strike in front of the Chinese Embassy in Seoul. The Parliamentary Forum for Democracy encompassing 18 countries has urged its members to raise the matter with their governments.

The case, however, is situated at the tip of the iceberg. According to the State Department’s Human Rights Report (2010), there may be thousands or tens of thousands of North Koreans hiding in China. Although China does allow large numbers of North Koreans to reside illegally in its country, they have no rights and China has forcibly returned tens of thousands over the past two decades. Most if not all have been punished in North Korea and according to the testimonies and reports received by the Committee for Human Rights, the punishment has included beatings, torture, detention, forced labor, sexual violence, and in the case of women suspected of become pregnant in China, forced abortions or infanticide.

Stringent punishment in particular has been meted out to North Koreans who have associated abroad with foreigners (i.e., missionaries, aid workers or journalists) or have sought political asylum or tried to obtain entry into South Korea. The North Koreans currently arrested and threatened with return are therefore likely to suffer severe punishment should they be repatriated. Some might even face execution; the North Korean Ministry of Public Security issued a decree in 2010 making the crime of defection a “crime of treachery against the nation.”

The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, a Washington DC-based non-governmental organization, established in 2001, has published three in-depth reports on the precarious plight of North Koreans in China and the cruel and inhuman practice of forcibly sending them back to one of the world’s most oppressive regimes. The first, The North Korean Refugee Crisis: Human Rights and International Response (2006), edited by Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, establishes that most if not all North Koreans in China merit a prima facie claim to refugee or refugee sur place status. The second, Lives for Sale: Personal Accounts of Women Fleeing North Korea to China (2010) calls upon China to set up a screening process with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to determine the status of North Koreans and ensure they are not forcibly returned. The third, to be published in April, Hidden Gulag second edition, by David Hawk, presents the harrowing testimony of scores of North Koreans severely punished after being returned to North Korea.

Reasons North Koreans in China should be considered refugees

Although China claims that North Koreans in its country are economic migrants subject to deportation, we submit that North Koreans in China should merit international refugee protection for the following reasons:

First, a definite number of those who cross the border can be expected to do so out of a well founded fear of persecution on political, social or religious grounds. It is well known that in their own country North Koreans suffer persecution if they express or even appear to hold political views unacceptable to the authorities, listen to foreign broadcasts, watch South Korean DVDs, practice their own religious beliefs, or try to leave the country. Some 200,000 are incarcerated in labor camps and other penal facilities on political grounds. Moreover, North Koreans imprisoned for having gone to China for food or employment often try, once released, to leave again. Some conclude they will always be under suspicion, surveillance and persecution in North Korea and therefore cross the border once again, this time seeking political refuge, ultimately in South Korea.

Because China has no refugee adjudication process to determine who is a refugee and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has no access to North Koreans at the border, it has not been possible to ascertain how many North Koreans are seeking asylum because of a well-founded fear of political or other persecution. But those who cross the border because of political, religious or social persecution will no doubt fit the definition of refugee under the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol.[1]

Second, those who cross the border into China for reasons of economic deprivation, probably the majority, may also qualify as refugees if they have been compelled to leave North Korea because of government economic policies that could be shown to be tantamount to political persecution. These North Koreans are not part of the privileged political elite and therefore have insufficient access to food and material supplies. In times of economic hardship in particular, food is distributed by the government first to the army and Party based on political loyalty whereas many of the North Koreans crossing into China during periods of famine are from the “impure,” “wavering” or “hostile” classes, which are the poor, deprived lower classes, designated as such under North Korea’s songbun caste system.[2] Their quest for economic survival could therefore be based on political discrimination and persecution. Examining such cases in a refugee determination process might establish that certain numbers of North Koreans crossing into China for economic survival merit refugee status under the 1951 Convention.

Third, and by far the most compelling argument why North Koreans should not be forcibly returned is that most if not all fit the category of refugees sur place. As defined by UNHCR, refugees sur place are persons who might not have been refugees when they left their country but who become refugees “at a later date” because they have a valid fear of persecution upon return. North Koreans who leave their country because of economic reasons have valid reasons for fearing persecution and punishment upon return. Their government after all deems it a criminal offense to leave the country without permission and punishes persons who are returned, or even who return voluntarily. North Koreans in China therefore could qualify as refugees sur place.

The High Commissioner for Refugees, Antonio Guterres in 2006 while on a visit to China raised the concept of refugees sur place with Chinese officials. He told them that forcibly repatriating North Koreans without any determination process and where they could be persecuted on return stands in violation of the Refugee Convention. To UNHCR since 2004, North Koreans in China without permission are deemed “persons of concern,” meriting humanitarian protection.[3] It has proposed to China a special humanitarian status for North Koreans, which would enable them to obtain temporary documentation, access to services, and protection from forced return. To date, China has failed to agree to this temporary protected status.

While China has cooperated with UNHCR in making arrangements for Vietnamese and other refugees to integrate in China or resettle elsewhere, it has refused to cooperate when it comes to North Koreans. Only in cases where North Koreans have made their way to foreign embassies or consulates or the UNHCR compound in Beijing has China felt impelled to cooperate with governments or the UNHCR in facilitating their departure to South Korea or other countries. In the vast majority of cases, China considers itself bound to an agreement it made with North Korea in 1986 (the “Mutual Cooperation Protocol for the Work of Maintaining National Security and Social Order and the Border Areas”). This agreement obliges China and North Korea to prevent “illegal border crossings of residents.” Chinese police as a result collaborate with North Korean police in tracking down North Koreans and forcibly returning them to North Korea without any reference to their rights under refugee or human rights law or the obligations of China under the agreements it has ratified. Implementation of this agreement sounds remarkably like the efforts made by the former Soviet Union to support the German Democratic Republic’s actions to punish East Germans for trying to leave their country. It is an agreement that undermines and stands in violation of China’s obligations under the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (which it signed in 1982), its membership in UNHCR’s Executive Committee (EXCOM), which seeks to promote refugee protection, and the human rights agreements to which China has chosen to adhere. So too do China’s domestic laws contradict its international refugee and human rights commitments. A local law in Jilin province (1993) requires the return of North Koreans who enter the province illegally.

China is bound not only by the Refugee Convention that prohibits non-refoulement but the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment,

which China ratified in 1988. It prohibits the return of persons to states “where there are substantial grounds for believing” that they would be “subjected to torture.” Indeed, the Committee against Torture (CAT), the expert body monitoring the convention’s implementation, has called upon China to establish a screening process to examine whether North Koreans will face the risk of torture on return, to provide UNHCR access to all North Korean persons of concern, and to adopt legislation incorporating China’s obligations under the convention, in particular with regard to deportations.

Another UN expert body, the Committee on the Rights of the Child, which monitors compliance by China and other states with the Convention on the Rights of the Child, similarly has called on China to ensure that no unaccompanied child from North Korea is returned to a country “where there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of irreparable harm to the child.”

China of course has legitimate interests in wanting to control its borders. It is concerned about potential large scale outflows from North Korea and the impact of such flows on North Korea’s stability. It also is said to be concerned about potential Korean nationalism in its border areas where there are historic Korean claims. But China should not become complicit in the serious human rights violations perpetrated by North Korea against its own citizens. The reports of the United Nations Secretary-General and of the Special Rapporteur on human rights in North Korea as well as the resolutions of the General Assembly, adopted by more than 100 states, have strongly criticized North Korea for its practices and called upon North Korea’s “neighboring states” to cease the deportation of North Koreans because of the terrible mistreatment they are known to endure upon return.

Recommendations

To encourage China to fulfill its international obligations in this matter, the following recommendations are offered:

First, additional hearings should be held by the United States Congress on the plight of North Koreans who cross into China. A spotlight must be kept on the issue to seek to avert China’s forced repatriation of North Koreans to situations where their lives are at risk.

Second, members of Congress should lend support to the efforts of the Parliamentary Forum for Democracy, established in 2010, so that joint inter-parliamentary efforts can be mobilized in a number of countries around the world on behalf of the North Koreans in danger in China. Such joint efforts can also offer solidarity to South Korean colleagues protesting the forced return of North Koreans.

Third, the United States should encourage UNHCR to raise its profile on this issue. It further should lend its full support to UNHCR’s appeals and proposals to China and mobilize other governments to do likewise in order to make sure that the non-refoulement provision of the 1951 Refugee Convention is upheld and the work of this important UN agency enhanced. China’s practices at present threaten to undermine the principles of the international refugee protection regime.

Fourth, together with other concerned governments, the United States should give priority to raising the forced repatriation of North Koreans with Chinese officials but in the absence of response, should bring the issue before international refugee and human rights fora. UNHCR’s Executive Committee as well as the UN Human Rights Council and General Assembly of the United Nations should all be expected to call on China by name to carry out its obligations under refugee and human rights law and enact legislation to codify these obligations so that North Koreans will not be expelled if their lives or freedom are in danger. Specifically, China should be called upon to adopt legislation incorporating its obligations under the Refugee Convention and international human rights agreements and to bring its existing laws into line with internationally agreed upon principles. It should be expected to call a moratorium on deportations of North Koreans until its laws and practices are brought into line with international standards and can ensure that North Koreans will not be returned to conditions of danger.

Fifth, the United States should promote a multilateral approach to the problem of North Koreans leaving their country. Their exodus affects more than China. It concerns South Korea most notably, which already houses more than 23,000 North Korean ‘defectors’ and whose Constitution offers citizenship to North Koreans. Countries in East and Southeast Asia, East and West Europe as well as Mongolia and the United States are also affected as they too have admitted North Korean refugees and asylum seekers. Together with UNHCR, a multilateral approach should be designed that finds solutions for North Koreans based on principles of non-refoulement and human rights and humanitarian protection. International burden sharing has been introduced for other refugee populations and should be developed here.

Sixth, the United States should make known its readiness to increase the number of North Korean refugees and asylum seekers admitted to this country.[4] Other countries should be encouraged as well to step forward and take in more North Korean refugees and asylum seekers until such time as they no longer face persecution and punishment in their country.

Thank you.

Roberta Cohen

[1] Under the Convention, a person is a refugee if he or she is outside his/her country of origin because of “a well-founded fear of being persecuted” for “reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” and unable or unwilling to avail him or herself of the protection of that country. An exception is if the person has committed criminal acts (although in the case of North Korea, the term criminal would be open to discussion).

[2] See Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, Marked for Life: Songbun, North Korea's Social Classification System, 2012 (forthcoming).

[3] In September 2004, the High Commissioner announced before UNHCR’s Executive Committee that North Koreans in China are ‘persons of concern.” One reason why UNHCR used this term was that it had no access to the North Koreans; another was that under the Refugee Convention, persons of dual nationality could be excluded from refugee status. (However it has been pointed out that in the case of North Koreans, not all are able to avail themselves of their right to citizenship in South Korea, some may not choose to do so, and South Korea may not take in every North Korean. The United States and other countries do not consider North Koreans ineligible for refugee status because of the dual nationality provision.)

[4] See Roberta Cohen, “Admitting North Korean Refugees to the United States: Obstacles and Opportunities,” 38 North, September 20, 2011.

This is the first satellite imagery report by HRNK on a long-term political prison commonly identified by researchers and former detainees as Kwan-li-so No. 18 (Pukch'ang). This report was concurrently published on Tearline at https://www.tearline.mil/public_page/prison-camp-18.

To understand the challenges faced by the personnel who are involved in North Korea’s nuclear program, it is crucial to understand the recruitment, education, and training processes through the lens of human rights. This report offers a starting point toward that understanding. North Korea’s scientists and engineers are forced to work on the nuclear weapons program regardless of their own interests, preferences, or aspirations. These individuals may be described as “moder

In this submission, HRNK focuses its attention on the following issues in the DPRK: The status of the system of detention facilities, where a multitude of human rights violations are ongoing. The post-COVID human security and human rights status of North Korean women, with particular attention to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). The issue of Japanese abductees and South Korean prisoners of war (POWs), abductees, and unjust detainees.

This report provides an abbreviated update to our previous reports on a long-term political prison commonly identified by former prisoners and researchers as Kwan-li-so No. 25 by providing details of activity observed during 2021–2023. This report was originally published on Tearline at https://www.tearline.mil/public_page/prison-camp-25.

This report explains how the Kim regime organizes and implements its policy of human rights denial using the Propaganda and Agitation Department (PAD) to preserve and strengthen its monolithic system of control. The report also provides detailed background on the history of the PAD, as well as a human terrain map that details present and past PAD leadership.

HRNK's latest satellite imagery report analyzes a 5.2 km-long switchback road, visible in commercial satellite imagery, that runs from Testing Tunnel No. 1 at North Korea's Punggye-ri nuclear test facility to the perimeter of Kwan-li-so (political prison camp) no. 16.

This report proposes a long-term, multilateral legal strategy, using existing United Nations resolutions and conventions, and U.S. statutes that are either codified or proposed in appended model legislation, to find, freeze, forfeit, and deposit the proceeds of the North Korean government's kleptocracy into international escrow. These funds would be available for limited, case-by-case disbursements to provide food and medical care for poor North Koreans, and--contingent upon Pyongyang's progress

For thirty years, U.S. North Korea policy have sacrificed human rights for the sake of addressing nuclear weapons. Both the North Korean nuclear and missile programs have thrived. Sidelining human rights to appease the North Korean regime is not the answer, but a fundamental flaw in U.S. policy. (Published by the National Institute for Public Policy)

North Korea’s forced labor enterprise and its state sponsorship of human trafficking certainly continued until the onset of the COVID pandemic. HRNK has endeavored to determine if North Korean entities responsible for exporting workers to China and Russia continued their activities under COVID as well.

George Hutchinson's The Suryong, the Soldier, and Information in the KPA is the second of three building blocks of a multi-year HRNK project to examine North Korea's information environment. Hutchinson's thoroughly researched and sourced report addresses the circulation of information within the Korean People's Army (KPA). Understanding how KPA soldiers receive their information is needed to prepare information campaigns while taking into account all possible contingenc

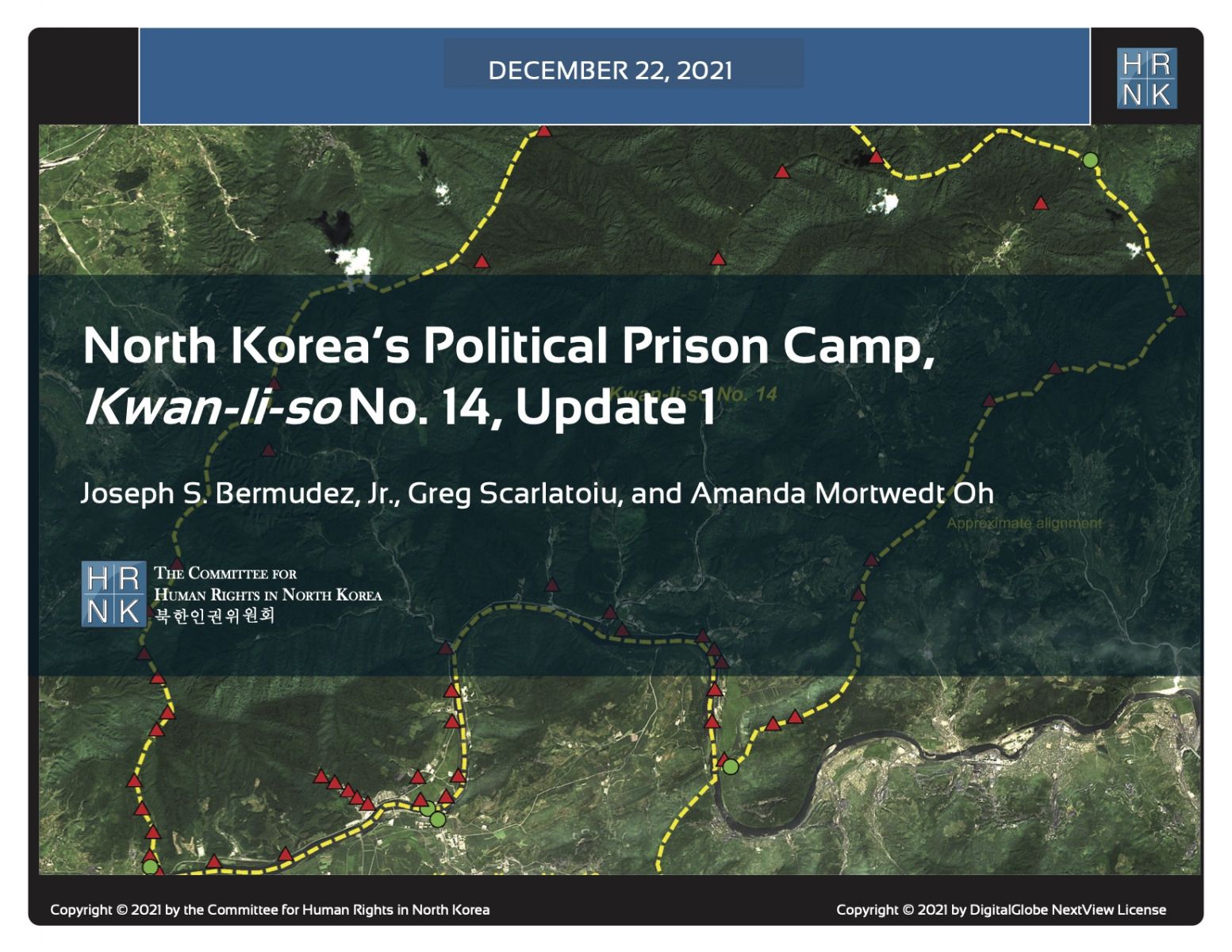

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by HRNK to use satellite imagery and former prisoner interviews to shed light on human suffering in North Korea by monitoring activity at political prison facilities throughout the nation. This is the second HRNK satellite imagery report detailing activity observed during 2015 to 2021 at a prison facility commonly identified by former prisoners and researchers as “Kwan-li-so No. 14 Kaech’ŏn” (39.646810, 126.117058) and

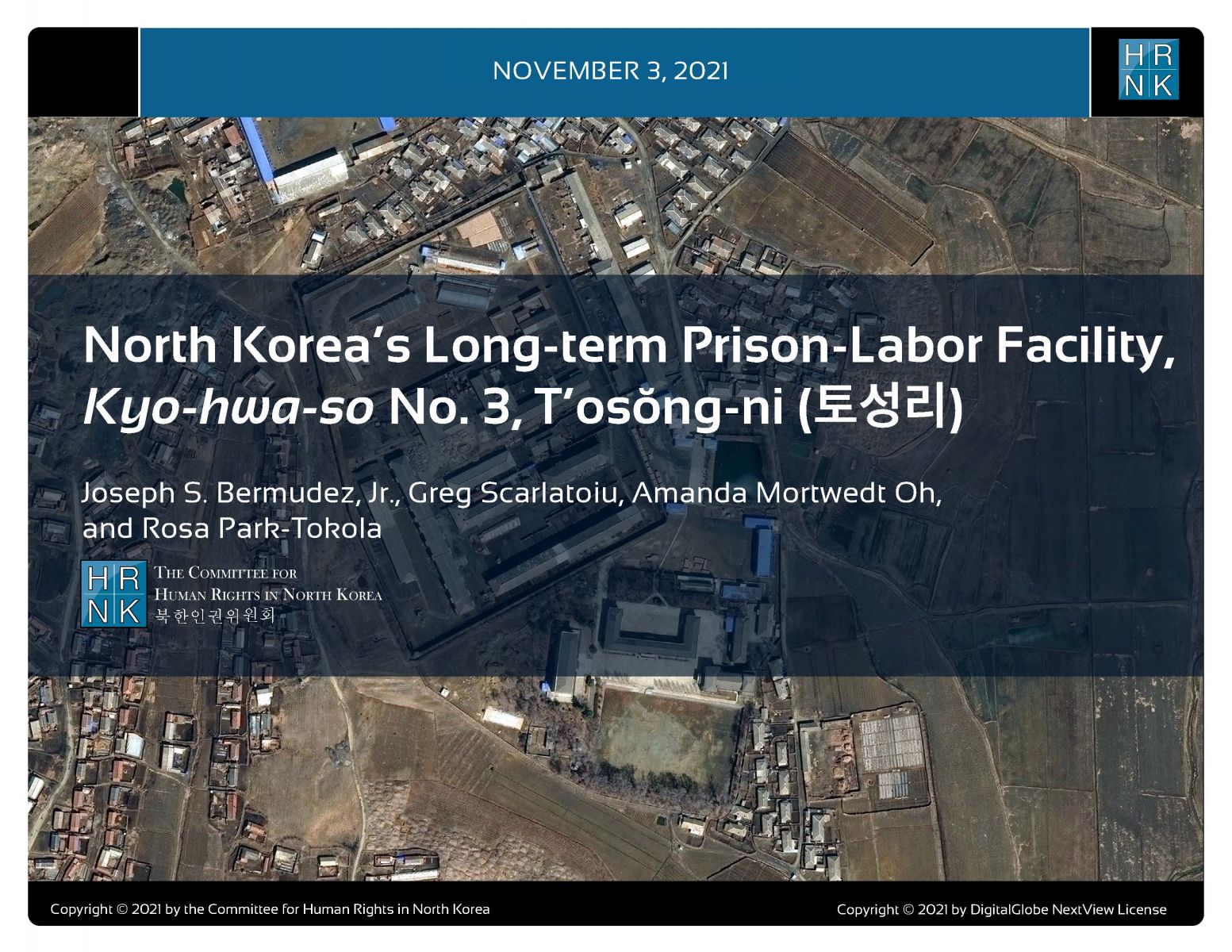

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by HRNK to use satellite imagery and former prisoner interviews to shed light on human suffering in North Korea by monitoring activity at civil and political prison facilities throughout the nation. This study details activity observed during 1968–1977 and 2002–2021 at a prison facility commonly identified by former prisoners and researchers as "Kyo-hwa-so No. 3, T'osŏng-ni" and endeavors to e

This report is part of a comprehensive long-term project undertaken by HRNK to use satellite imagery and former detainee interviews to shed light on human suffering in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, more commonly known as North Korea) by monitoring activity at political prison facilities throughout the nation. This report provides an abbreviated update to our previous reports on a long-term political prison commonly identified by former prisoners and researchers as Kwan-li-so

Through satellite imagery analysis and witness testimony, HRNK has identified a previously unknown potential kyo-hwa-so long-term prison-labor facility at Sŏnhwa-dong (선화동) P’ihyŏn-gun, P’yŏngan-bukto, North Korea. While this facility appears to be operational and well maintained, further imagery analysis and witness testimony collection will be necessary in order to irrefutably confirm that Sŏnhwa-dong is a kyo-hwa-so.

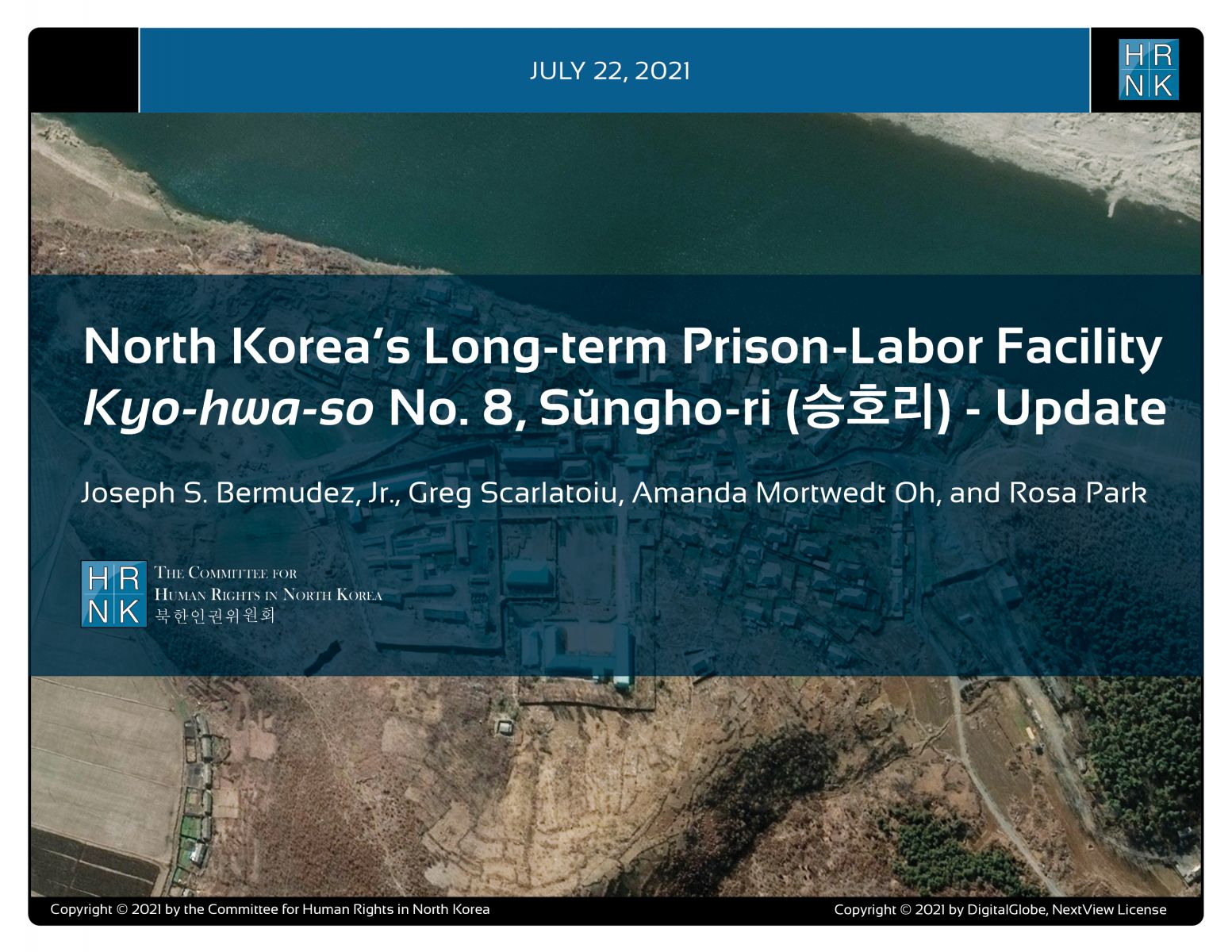

"North Korea’s Long-term Prison-Labor Facility Kyo-hwa-so No. 8, Sŭngho-ri (승호리) - Update" is the latest report under a long-term project employing satellite imagery analysis and former political prisoner testimony to shed light on human suffering in North Korea's prison camps.

Human Rights in the Democratic Republic of Korea: The Role of the United Nations" is HRNK's 50th report in our 20-year history. This is even more meaningful as David Hawk's "Hidden Gulag" (2003) was the first report published by HRNK. In his latest report, Hawk details efforts by many UN member states and by the UN’s committees, projects and procedures to promote and protect human rights in the DPRK. The report highlights North Korea’s shifts in its approach

South Africa’s Apartheid and North Korea’s Songbun: Parallels in Crimes against Humanity by Robert Collins underlines similarities between two systematically, deliberately, and thoroughly discriminatory repressive systems. This project began with expert testimony Collins submitted as part of a joint investigation and documentation project scrutinizing human rights violations committed at North Korea’s short-term detention facilities, conducted by the Committee for Human Rights